As newspapers and television broadcasts continue to be filled with daily news from the 2024 General Election, in today’s blog for the Georgian elections project Dr Robin Eagles turns his attention to the role of the press in 18th century election campaigns...

Relations between Parliament and the press in the 18th-century were often strained. Strictly speaking, it was a breach of privilege for the details of parliamentary debate to be reported for much of the period, although that did not prevent some from doing so. It was not until the 1770s that restrictions on reporting debates were lifted but even then, one could not expect to see everything said in Parliament reproduced faithfully in print.

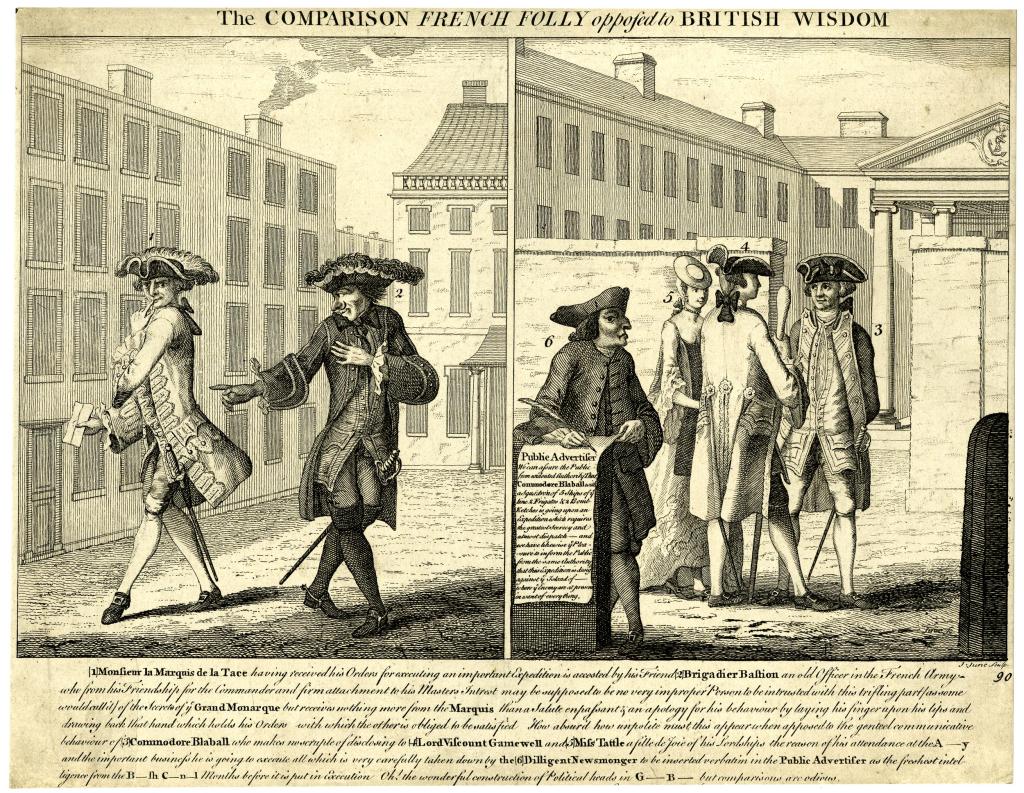

© The Trustees of the British Museum

As one print satire from 1757 showed, concerns about the tendency of newspapers to leak important information went well beyond the confines of Westminster. At times of war there were concerns about the tendency of members of the establishment to blab, enabling journalists to circulate what ought to have been kept secret.

As far as accuracy went, while some parliamentary speeches were reported accurately, this was not always the case. Sometimes, MPs (like John Wilkes) leaked their speeches in advance, though it is never clear whether what was then said reflected what was printed. On other occasions, reporters might simply make things up. Certainly, Samuel Johnson said as much when attending a dinner party. He claimed that when he was working as a reporter for Edward Cave, editor of the Gentleman’s Magazine, he used to compose his reports from home based on scanty details of who had said what. The only thing he was always careful to ensure was that ‘the Whig dogs should not have the best of it’. [Sparrow, 15-16]

If reporting what went on within Parliament was a difficult subject before the 1770s, elections and pre-electoral manoeuvring offered to the press much more scope for reporting on politics. Then, as now, different papers had different political loyalties. This meant that one, inevitably, got a different view of events and of the causes in play depending which paper one happened to read. There was also plenty of not always very friendly rivalry between the different offerings, with some not refraining from insulting organs representing the other side. For instance, in 1734 the Whig-leaning Daily Courant could not stop itself from laying into its anti-Walpole rival, the London Evening Post:

the London Evening Post of last Night, has, in the usual Strain and Spirit of that Paper, endeavoured to make up in abuse and scurrility, what is wanting in truth and argument… [Daily Courant, 4 May 1734]

The general election of that year was dominated by the aftermath of Sir Robert Walpole’s efforts to pass the Excise the previous year. This was reflected in many of the contests fought in various constituencies, where previously elections had been settled with one candidate returned from each party. For example, in Essex, formerly shared between one Tory and one Whig, two Tories succeeded in forcing the solitary Whig candidate into third place. This was celebrated in the London Evening Post, seeing it as the triumph of independent freeholders over the many office-holders who lived in the county, an example it hoped might be imitated elsewhere:

So great a majority in a county where such numbers of place-men and dependants reside, shews the honesty of the freeholders, and their aversion to all those that voted for Standing Armies, Excise, &c. Here the Freeholders elected Men of integrity and Capacity to serve their Country, without a View to either Place or Pensions… [London Evening Post, 7-9 May 1734]

While the London Evening Post celebrated such opposition successes, though, the Daily Courant had already questioned what it was they were ultimately hoping to achieve:

If nothing but alterations will satisfy those given to change, let us ask them, since we enjoy Peace, Liberty, and Property already, what it is they design to give us more? [Daily Courant, 27 April 1734]

Irrespective of their political stances, newspaper reporting of 18th-century elections underscored the liveliness of the occasions, even in places where there was no formal contest. There was often pageantry, with Tory supporters appearing with ‘oaken boughs in their hats’ to distinguish themselves from supporters from the other parties. There was always plenty of food and drink on offer, too, and often a lively festive atmosphere. Sometimes, though, things got out of hand, as happened at Maldon in Essex in 1734 after it became apparent that the Tory (and suspected Jacobite), Thomas Bramston, one of the sitting members, would not win there. At that point, according to the Daily Courant:

the Rabble that attended him into Town, became so riotous and unruly, that they flung stones at the two other candidates as they stood on the Hustings, and assaulted all that voted for them in so violent and outrageous a manner, that in all probability a great deal of mischief would have been done, and, perhaps, some lives have been lost, if the magistrates had not read the proclamation [the Riot Act], which dispersed them… [Daily Courant, 4 May, 1734]

Unsuccessful in Maldon, Bramston managed to get elected, instead, for the county, retaining his seat until Henry Pelham’s snap election in 1747.

RDEE

Further Reading:

Andrew Sparrow, Obscure scribblers: A History of Parliamentary Journalism (2003)

Find more blogs and videos from our Georgian Elections Project here.