In this blog, Dr Alex Beeton from our House of Lords 1640-1660 project explores a little-used parliamentary source – the ‘Scribbled Books’ – and reveals some of the important information that can be found within them…

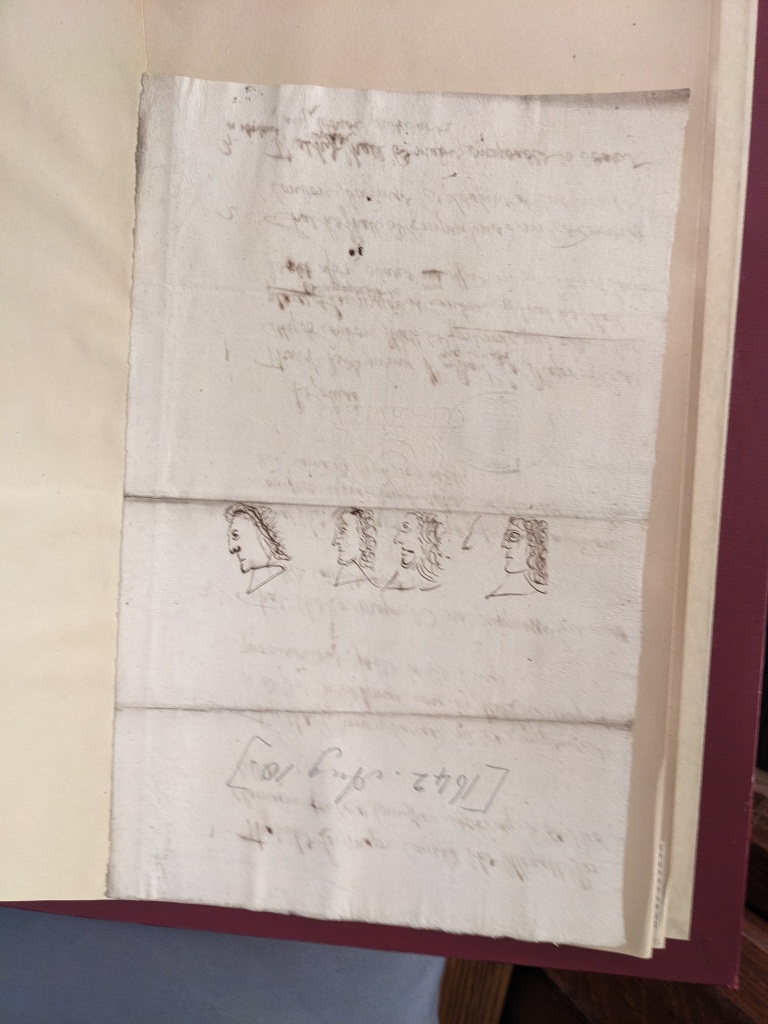

John Browne, the Clerk of the Parliaments (i.e. the House of Lords) in the Long Parliament, did not have an easy job. His primary purpose was, with the help of a team of assistants, to write the Journal of the House of Lords, the official record of the House’s daily business. The journal was not a verbatim account of what was said and done and forging the final product was a lengthy and convoluted affair which began with rough notes being made in the House. In the early Stuart Parliaments, it appears that these jottings were entered into something called a ‘Scribbled Book’. Browne seems to have broken with this practice and instead made his entries in the Scribbled Book after the day’s sitting, basing them on hurried notes made on loose sheets. However, like those of his predecessors, Browne’s Scribbled Books are essentially the first version of what would become the journal and much of the material they contained was never transferred to the finished product. They are a treasure trove of information for historians of the British Civil Wars.

The eight surviving Scribbled Books of the Long Parliament, ranging from November 1640-April 1642, have long been known of by scholars but have never been investigated in their own right. The History of Parliament’s House of Lords 1640-1660 section is currently working through these volumes, bringing to light new detail but also using them to explain how the journals were constructed. The latter task is especially important since, with the notable exception of Elizabeth Read Foster’s work, there is relatively little research into how these important records were created. There was no official rubric for making the journals, though there were some traditions which a previous clerk, Robert Bowyer, helpfully summarised:

The Clerk of the Parliament doth every day (sitting in the House or Court) write into his rough or scribbled book, not only the reading of the Bills and other proceedings of the House. But as far forth as he can, whatsoever is spoken worthy of observation. Howbeit into the Journal Book, which is the record, he doth, in discretion, forbear to enter any things spoken, though memorable, yet not necessary or fit to be registered and left to posterity of record.

Catalogue of Manuscripts in the Library of the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, ed. J.C. Davies (3 vols, Oxford, 1972), ii. 612

Browne appears to have shared Bowyer’s concern with omitting embarrassing details from the journal. His Scribbled Books contain many details of physical brawls or verbal slugging matches which, sadly for those reading them, did not make it into the journal.

Along with discretion, the other key guiding principle behind the construction of the journal was brevity. The journals of both Houses were intended to be user friendly. MPs, Lords, interest groups, and private citizens all needed to be able to locate relevant entries and to navigate the material quickly. One of the most notable revelations of the Scribbled Books is the degree to which Browne summarised business in order to meet these needs. In reality, business in the House dripped rather than flowed. Often, topics were discussed before being dropped due to an interruption or not concluded by the end of the day’s sitting. To overcome the obstacles, Browne tended to condense. Speeches were summarised and business which had fitfully dealt with over the course of the day or even several days was shortened into a brief, sequential summary. In the pursuit of conciseness and respectability much of the actual business conducted by the Lords fell onto the cutting room floor when the journals were written. Much of this lost evidence is of an inconsequential nature but a great deal of it is not and is of enormous interest to scholars of the English Revolution.

To give one significant example of the evidence which can be found in the Scribbled Books, we might look at the events of 28 December 1641. It was not a tranquil time at Westminster. Tumultuous crowds, aggressively calling for the exclusion of bishops from the Lords, milled about the Parliament house. There was a significant political dimension to these protests: the removal of the prelates would break the king’s party in the upper house, removing a significant obstacle to the anti-Caroline junto. In a febrile atmosphere, the Lords’ journal baldly records a vote being held over whether the Parliament was free. This was a highly significant moment in the prelude to the Civil Wars. Had the Lords decided that Parliament was not free then Parliament would have effectively ceased operations giving Charles control of the political scene. Historians since Gardiner have discussed it at length. They have also dwelt on the role of George Lord Digby since it was he who supported the motion with an impassioned speech in which he took several digs at the MPs encouraging the crowds and, in the report of one witness, ‘bespattered the House of Commons as much as one would do his cloak in riding from Ware to London’. (HMC Montagu, p. 137) Accordingly, it was on Digby, a parliamentarian ‘hate figure’ and advisor of the king, that the ire of the Commons was focussed the next day.

However, the Scribbled Book and other notes kept by Browne present a much more complicated image. It appears that Digby did indeed make the original motion, prompting the House to adjourn itself into a committee (a procedure which allowed members to speak freely and as much as they liked to an issue) during which Thomas Wriothesley, 4th earl of Southampton, actually proposed the question of whether the House was free or not. The Lords then resumed their sitting in order to vote on Southampton’s question. It was this vote which was then recorded in the journal. Browne, desirous of a concise summary, had cut out all the fat and simply left a record of the final vote without the convoluted process by which it was reached. In the process, the extremely revealing actions of Southampton were concealed. Southampton had been drifting towards the king’s camp before 28 December and his actions were further evidence of a political realignment. His intervention was as provocative as Digby’s but seems to have been overlooked by the Commons due to their antipathy towards the latter and desire to remove one of Charles’s most belligerent advisors from the king’s counsel. However, one person who did not ignore the earl’s actions was the king: two days later Southampton was rewarded for his endeavours by being made a Gentleman of the Bedchamber.

These and many other important facts about the Lords are contained in the Scribbled Books but are little known. Their recovery has the potential to illuminate the House of Lords which is by far the more dimly lit of the two parliamentary chambers in modern historiography. A greater awareness of what occurred in the Upper House and the actions of individual peers does not just improve historians’ understandings of a few lords. As is now widely acknowledged, parliamentary politics was fundamentally bicameral with events in both Houses closely connected. This point is evident in the Southampton/Digby episode. Both peers were implicitly attacking the Commons-men and their allies in the Lords who tried to dominate the Parliament through mob-intimidation. The attack by the Commons on Digby rather than Southampton reflected the belief of the anti-Caroline faction that it was the former who was the more serious threat to their actions and so needed to be removed in order to facilitate the erosion of the royalist roadblock in the Lords. As this brief example suggests, the Scribbled Books reveal much about the Lords. A greater understanding of the Lords allows in turn a better comprehension of parliamentary affairs as a whole, an understanding which is not always helped by the Houses’ journals which tend to be curt, formulaic, and impersonal and so suppress the more messy, eventful, and revealing reality of mid-seventeenth century politics.

A.B.

Note:

Browne’s record of 28 December 1641 can be found in: Parliamentary Archives, BRY/90 and BRY/93 (entries for 28 December 1641).

Further reading:

Elizabeth Read Foster, The House of Lords 1603-1649, Structure, Procedure, and the Nature of It Business (London, 1983).

Elizabeth Read Foster, ‘The Journal of the House of Lords for the Long Parliament’, in Barbara C. Malament (ed.), After the Reformation: Essays in Honor of J.H. Hexter (Philadelphia, 1980), pp. 129-146

John Adamson, The Noble Revolt: The Fall of Charles I (London, 2007).