Dr Kathryn Rix, of the Victorian Commons, tells us about the very first election by secret ballot in Britain…

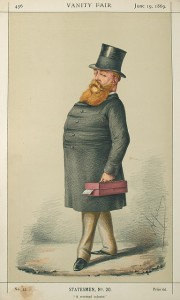

Today marks the anniversary of the first occasion on which the secret ballot was used to elect a British MP, under the provisions of the 1872 Ballot Act. The poll, held in the Yorkshire borough of Pontefract on 15 August 1872, was ‘watched with considerable curiosity’ throughout the country. This by-election, prompted by the requirement that the borough’s Liberal MP, Hugh Childers, should seek re-election after being appointed to ministerial office, would not otherwise have generated much interest: although he faced a Conservative opponent, there was little doubt that Childers would be victorious. However, the opportunity to see the new electoral machinery in action meant that election agents from all over the country flocked to the constituency, and the contest was widely reported in the press. Curiously, Childers had already had the experience of being elected by this method, having served as a member of the Legislative Assembly in Victoria, Australia, the first legislature in the world to adopt the secret ballot (in 1856).

The system of open voting, under which British elections were conducted until 1872, has been described by Philip Salmon on our Victorian Commons blog. Pontefract’s electors still came to vote at a polling booth, but these now provided separate compartments where voters could mark their ballot papers in private, in a similar way to modern practice. (One notable difference from today was that ballot papers did not list the names of the parties to which candidates belonged.) The secret ballot’s first trial was generally deemed to be a success, with very few spoilt papers. Despite a delay in conveying ballot boxes from the outlying district of Knottingley, the mayor, who acted as returning officer, announced the result just four hours after the poll closed. One of the original ballot boxes still survives: rather quirkily, it was sealed using a liquorice stamp from a local factory where Pontefract cakes were produced!

The new system did not operate entirely smoothly. There were reports of ‘bewildered’ voters being ‘coached’ by party activists on how to mark their papers, and three elderly voters who forgot their spectacles had to be assisted using the procedure for blind voters. With the writ for the election being issued only three weeks after the Ballot Act had passed, there had been little time for preparations. This resulted in some rather imperfect arrangements: at one polling station, ill-fitting boards meant that voters could see between the compartments. Pontefract’s town hall could no longer be used for polling, as it lacked a separate entrance and exit, and in a hastily adapted schoolroom, voters had to leave through a window which had been knocked out, with rather wobbly boards leading to the playground below. The Times reported the unexpectedly comical result:

The voter, full of grave and serious thoughts at having assisted at so important an experiment, found himself involuntarily running with an ever-increasing impetus down a steep incline on a spring board which would have enabled a professional gymnast to clear the school wall with the greatest ease.

Although such hurried arrangements could be rectified in future, another more significant problem emerged: the high proportion of illiterate voters, totalling 199 of the 1,236 who polled. They slowed down proceedings, as not only did a special declaration have to be made regarding their status, but also the room had to be cleared of any other voters and of the attendant policemen, before their votes could be given orally and their papers marked accordingly with the assistance of election officials. After the election, Pontefract’s mayor suggested how this process might be speeded up, particularly for the benefit of larger constituencies, although he noted that Pontefract had a greater than average number of illiterates due to its rural population.

The general impression of the new system was positive, with Childers among those rejoicing that the secret ballot had proved ‘thoroughly workable’. In contrast with the unruly behaviour which had often marred previous elections, seasoned observers declared that ‘they never saw a contested election in which less intoxicating liquor was drunk’ and there were no allegations of bribery or other corrupt practices. So quiet and orderly was the town that ‘it hardly seemed like an election’.

The changed atmosphere of the electoral contest owed a great deal to another key reform introduced in 1872: the abolition of public nominations. Instead of being proposed and seconded and then speaking before a large crowd at the hustings, the candidates handed in their nomination papers privately and unceremoniously at Pontefract town hall. Unlike the festive atmosphere of previous nominations, ‘hardly any one left his work or business’. This did, however, remove an important opportunity for participation in election proceedings by non-voters, including women, undermining the assumption that the 1872 Ballot Act was a straightforwardly ‘democratic’ measure.

If the experience of Pontefract in 1872 suggested that elections would in future be rather unexciting affairs and free from corruption, this was a mistaken impression. Candidates may no longer have greeted hustings audiences, but election meetings became increasingly important as an opportunity for the public to see their would-be representatives face-to-face. More ominously, the election agents who came to observe at Pontefract suggested that bribery would be perfectly possible under the ballot. This proved to be the case, with the notoriously corrupt general election of 1880 prompting major legislation in 1883 to tackle the continued problem of electoral corruption.

K.R.

All quotations are taken from The Times.

7 thoughts on “‘Watched with considerable curiosity’: The first secret ballot in Britain, 15 August 1872”