In October, Dr Hannes Kleineke, editor of our Commons 1461-1504 project, delivered the ‘Maurice and Shelagh Bond Memorial Lecture’ at St George’s Chapel. In a series of two blogs, Hannes reflects on the people of St George’s Chapel, beginning with a look back to the mid-fifteenth century and the position of the clerk, a role that Maurice Bond served for 36 years.

Annually in October, a lecture is given at St George’s Chapel in Windsor castle to celebrate the memory of Maurice Bond, for many years the official custodian of the records of the dean and canons, and his wife Shelagh, who served alongside him as honorary archivist. Maurice Bond is, however, also remembered at Westminster, where he served as clerk of the records to the House of Lords from 1946 until his retirement in 1981.

When the then 30-year-old Maurice Bond took up the clerkship of the records at the House of Lords, it was still a relatively new post, having been created only in February of the same year, when Francis Needham, formerly an assistant librarian in the Bodleian, had been appointed to it. The Palace of Westminster at this time still bore the scars of German bombing. The parliamentary records had during the war been evacuated to Laverstock House in Wiltshire, where they had been stored in less than ideal conditions. Needham’s first task was thus to return them to their proper home at Westminster. To re-organise the dark and dirty interior of the Victoria Tower where the records were traditionally kept, proved too much for him, and Needham consequently tendered his resignation after just a few months in post. As a final task before leaving, he was charged by the Clerk of the Parliaments of the day, Sir Henry Badeley, to find a successor. Needham approached the distinguished medievalist, Alexander Hamilton Thompson, formerly professor of medieval history at the university of Leeds, and it was he who recommended the young Mr Bond.

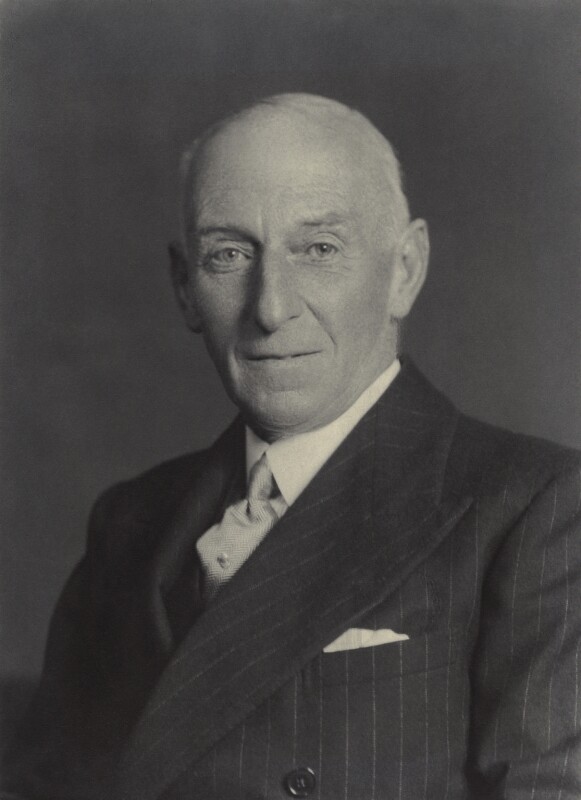

by Walter Stoneman (1937)

(c) NPG

The creation of a dedicated parliamentary record office had been recommended by an official report in 1937, little had been done, and Bond set about his task with enthusiasm and, in the words of one observer, a ‘flair [that] had the characteristic of an entrepreneur’. Over a period of fifteen years, seven new floors, equipped with modern air conditioning units were constructed in the Victoria Tower, while Maurice Bond and his staff not only carried out vital listing and conservation work, but also kept the enthusiasm of parliamentarians in both houses alive with a programme of exhibitions and lectures. In 1963, finally, the new record office was opened to great acclaim.

Bond’s appointment at Westminster renewed a connexion between Parliament and the College of St George that had first come into being in the mid 15th century. This connexion was first established as a direct result of the appointment in 1447 of a Chancery clerk called John Faukes as clerk of the Parliaments.

John Faukes is thought to have come from Worcestershire, and had found employment in the royal Chancery by the later years of the reign of Henry IV. His ecclesiastical career, by contrast, was in the first instance centred in Sussex, which may have provided easy access to Westminster. He had become involved in parliamentary affairs in the 1430s, when he was repeatedly named among the clerks assigned at the beginning of each assembly to receive petitions from all comers. In 1439 he was appointed chancellor of Chichester cathedral, and two years later he became dean of the collegiate church of St Mary in the Castle at Hastings.

(c) G. Laird

Having become clerk of the Parliaments in the reign of Henry VI, Faukes might have been dismissed on Edward IV’s accession, as some of his successors were during subsequent changes of dynasty. But Edward recognised his ability and not only confirmed him in post, but also promoted him from the deanery of Hastings to the more prestigious one of Windsor, which Faukes would retain until his death nearly ten years later.

But Faukes’s longevity alone does not account for his importance in the history of the medieval Parliament. Faukes was an administrative innovator, whose work has shaped the process of parliamentary record keeping to the present day. The parliament rolls of the middle ages were little more than a record of the acts that had passed, along with some procedural notes of matters like prorogations or the appointment of the Commons’ speaker. Faukes faithfully continued this practice, and oversaw the creation of a total of ten parliament rolls.

But he went further. From early on in Faukes’s clerkship, we begin for the first time to have a record of attendances in the House of Lords, with some terse notes on the discussions that took place: these are direct precursors of the modern journals of the houses of commons and lords, which contained similar material, albeit over the centuries in an increasingly detailed form. Sadly, none of Faukes’s originals survive, but we do have early modern copies of several fragments, dating from the 1450s to 1461. These compilations were in the first instance Faukes’s private records of proceedings which would only acquire an official character in a later period, and they may tell us a little about the man’s own orderly mindset and penchant for record keeping.

There is also a second body of parliamentary records from Faukes’s day, which is interesting for a different reason. The documents in question are a collection of exemptions from the provisions of one or other of the repeated acts of resumption passed by Parliament in the course of the 15th century. These were acts based on the view that the King should be able to live comfortably off the revenues of the Crown estates, provided that he did not grant away too many of them by way of reward. The acts thus cancelled all royal grants before a given date and took the property or annuity back into the King’s hands. The King was, however, accorded the power to exempt individual grantees from the resumption of all or some of their grants, and suitors in their droves routinely petitioned for such exemptions, which are generally known as ‘provisos’.

To gain such a proviso (or bill of exemption), an individual or corporate body would have it written out, and needed to present the document for personal approval to the King, which, assuming that it was forthcoming, was usually indicated by the monarch’s hand-written initials, or on other occasions a token, such as a ring. The successful suitor would then take this slip of parchment to the clerk of the Parliaments for enrolment on the Parliament roll in an appendix to the act of resumption.

What makes these relatively mundane documents, which survive in their hundreds, interesting are the notes that Faukes scribbled on them, indicating where he had received them. It is not entirely clear why he would have wanted to record this information, although we may speculate that it perhaps formed part of his personal filing system. Along with, perhaps, another insight into his mindset, it also offers us a glimpse, however limited, of the busy and peripatetic life that the clerk of the parliaments led during the sessions. His normal place of work during this time was the Parliament chamber in the palace of Westminster, and here he took delivery of the majority of the documents filed by him, while others were delivered to his own house. On a number of days, he visited the King’s own chamber, and even the more private spaces of the monarch’s closet and oratory. At other times he was found in St Stephen’s chapel and the meeting place of the House of Commons in the refectory of nearby Westminster abbey, on his way between these various locations being accosted by further supplicants in the abbey cloisters and Westminster Hall.

Nor, for that matter, did the deanery at Windsor afford Faukes much privacy: his movements during the Parliament of 1467 are less well documented than those of two years earlier, but the journey to St George’s was clearly insufficiently onerous to deter all suitors. Faukes had by then ceased to keep a detailed record of where every individual bill of proviso was delivered to him, but he did note that a number of them had come to his hands at Windsor.

The towering figure of John Faukes, the expert administrator, easily dwarfs many of the men who succeeded him, but his death did not represent a sharp break of the ties between St George’s and Windsor. He was probably instrumental in recommending as his successor as clerk of the Parliaments a fellow canon, Baldwin Hyde, who duly assumed the office, but was forced to retire following the upheaval of Henry VI’s brief restoration. Richard III’s clerk of the Parliaments, Thomas Hutton, was likewise rewarded with a prebend at Windsor, but Richard’s defeat at Bosworth saw Hutton dismissed from office, and two years later he also resigned his place at St. George’s and retired to Lincoln. In the autumn of 1485, finally, the clerkship of the Parliaments and the deanery of Windsor were once more reunited in the hands of John Morgan, a Welsh-born second cousin of King Henry VII, and future bishop of St David’s.

H.W.K.

You can watch Dr Hannes Kleineke deliver his talk at the ‘Maurice and Shelagh Bond Memorial Lecture’, here.

Further reading:

G.R. Elton, ‘The early Journals of the House of Lords’, English Historical Review, lxxxix (1974).

Hannes Kleineke, ‘Parliaments and Procedures’, in The History of Parliament: The Commons 1422-61 ed. Linda Clark (7 vols., Cambridge, 2021).

Michael Hicks, ‘King in Lords and Commons: three insights into late-fifteenth-century parliaments 1461-85’, in People, Places and Perspectives ed. Keith Dockray and Peter Fleming (Stroud 2005).

Roger Virgoe, ‘A new fragment of the Lords’ Journal of 1461’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, xxxii (1959).

R.A. Griffiths, ‘The Winchester session of the 1449 Parliament: a further comment’, Huntingdon Library Quarterly, xlii (1979).

The Fane Fragment of the 1461 Lords’ Journal ed. W.H. Dunham (New Haven, 1935).

One thought on “From Windsor to Westminster: the People of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, in Parliament in the later Middle Ages and beyond”