Today, on 30 May 2024, Parliament will be formally dissolved following a ‘Dissolution proclamation’ from the King. This is the first time that this proclamation has been required since 201o, following the repeal of the Fixed Term Parliaments Act in 2011. But how was Parliament formally dissolved in the 18th century? In this blog, the first in our Georgian Elections series, Dr Robin Eagles from our Lords 1715-1790 project looks into the process…

On the death of George II in the autumn of 1760, Parliament was not dissolved and the new monarch, George III, inherited the assembly elected under his grandfather in 1754. This followed on from changes to the conventions about dissolving parliaments inaugurated by the 1707 Succession to the Crown Act, which enabled parliaments to continue in being for up to six months after the death of a sovereign. George III and his ministers took advantage of this provision, enabling them to delay dissolving Parliament until 20 March 1761. When George II had come to the throne in June 1727 he had also continued with his father’s old Parliament, but in that case, he had opted to dissolve much more promptly, just a few weeks later on 5 August.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

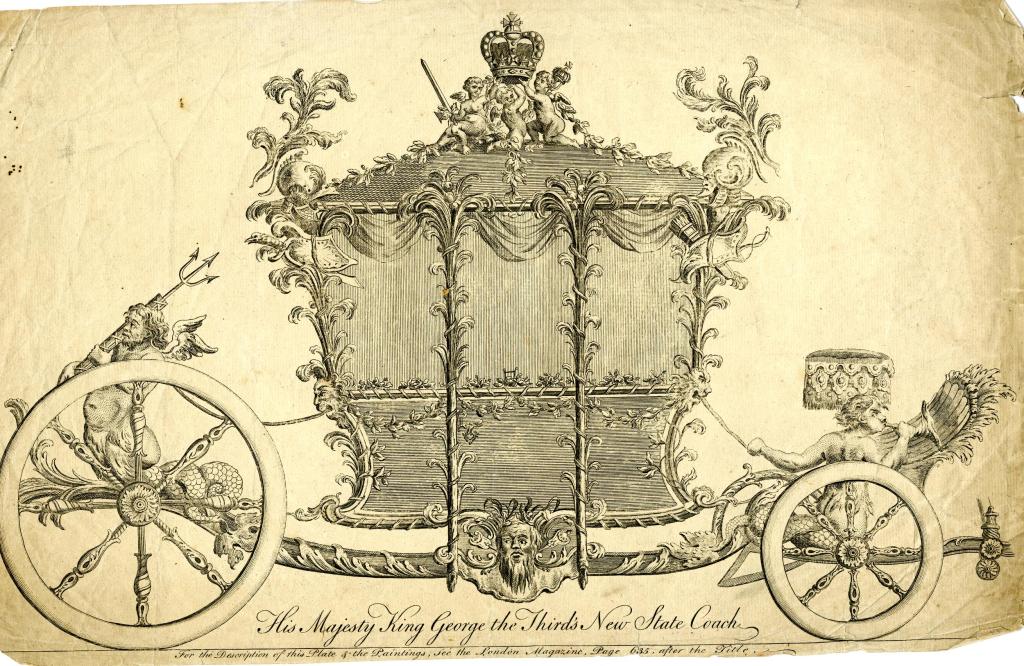

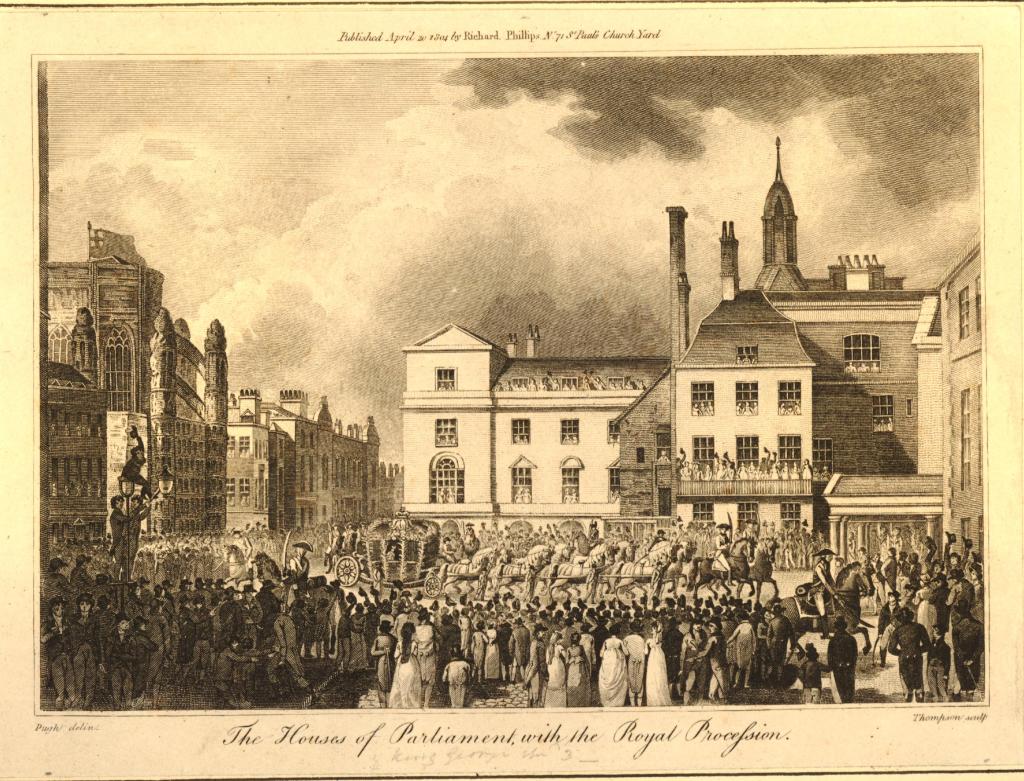

The day prior to the 1761 dissolution, the king attended Parliament in person, travelling to Westminster in his state coach and accompanied by his master of the horse and one of his gentlemen of the bedchamber. The presence of the king in the palace always drew a crowd, so orders were given out for clearing the Painted Chamber, the Lobby and the passage to the Lords so that the king and his party, as well as the Members could make their way to the chamber without being jostled. Having taken his place, the king gave the royal assent to 37 bills, which had managed to make it over the line in time, before speaking to both Houses, thanking them and drawing their attention to the imminent dissolution.

I cannot put an End to this Session, without declaring My entire Satisfaction in your Proceedings during the Course of it. The Zeal you have shewn for the Honour of My Crown, as well as for My true Interest and that of your Country, which are ever the same, is the clearest Demonstration of that Duty and Affection to My Person and Government, of which you so unanimously assured Me at your First Meeting. [LJ xxx. 99]

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The lord chancellor then prorogued Parliament to 7 April, though this was undone almost at once by the proclamation for a dissolution made out the following day. The text ‘discharged’ the Members from meeting on 7 April, and instead commanded the calling of ‘a new Parliament’ and made out order for writs to be issued for the elections.

The king may have been able to speak positively on this occasion of universal satisfaction but subsequent events were to make his tenure of the throne – and his relations with Parliament – far more taxing on occasion. This was particularly true when his first Parliament, which assembled on 19 May 1761, was dissolved on 11 March 1768. In his speech on 10 March, George III had again spoken of his people giving ‘fresh Proofs to their Attachment to the true Interest of their Country’ in the coming election and insisted that ‘The Welfare of all My Subjects is My first Object’. [LJ xxxii. 144] The resulting election campaign was, however, to be one of the most controversial of the century. Many seats were targeted by carpet-bagging Nabobs – wealthy men who had made their fortunes in the colonies and now returned home intending to buy their way into society. The most notorious campaigns, though, centred on the City of London and then on the county of Middlesex, where the notorious outlaw, John Wilkes, former MP for Aylesbury, had chosen to attempt to make a return to British politics after several years in exile. George III may have hoped always to be able to rely on Members who identified the interest of the country and Crown as one, but that was not always to be the case.

RDEE

Further reading:

Parliament and the demise of the crown, House of Lords Library

Find out more about the Dissolution of Parliament in 1784 in this video on the History of Parliament’s TikTok page!

And make sure to follow #GeorgianElectionsProject, as we post daily content going inside an 18th century election…