As part of our Queen Caroline series, Dr Martin Spychal, research fellow on the Commons 1832-1868, takes a look at the part played in the affair by the radical MP for London, Matthew Wood (1768-1843). A hop merchant and former Lord Mayor, Wood brought Caroline out of exile in June 1820 and housed her at his Mayfair residence at the beginning of the national crisis. As the affair gathered steam Wood became a prime target for loyalist vitriol, a prime example being Theodore Hooke’s malicious pamphlet Solomon Logwood: A Radical Tale. The pamphlet is currently on display as part of the Reform, React, Rebel exhibition at UCL, which was curated by Martin and Dr Vivienne Larminie.

From the perspective of the British establishment Matthew Wood came from lowly beginnings. He started his career as an assistant at his father’s chemist shop in Tiverton before moving to London as a travelling druggist during the 1790s. Wood struck gold in 1802 with an investment in a colouring agent for porter beer and soon became one of London’s major hop merchants. At the same time he was appointed to the City of London common council, and in 1809 was elected an alderman of the City and sheriff of Middlesex.

In 1815 Wood served a largely unprecedented two-year term as Lord Mayor of London. His popularity in the City increased during his mayoralty on account of his resistance to the government’s repressive post-Napoleonic legislation. Wood’s outspokenness only created enemies at Westminster, however, and for two years running ministers refused to attend his Lord Mayor’s dinner.

As his mayoralty drew to a close during 1817, he was elected a radical MP for London. Dogged by a ‘harsh, grating’ voice which sounded ‘the same whenever he speaks, or on whatever subjects he expresses his sentiments’, Wood continued to call out government repression and was a stringent critic of the government’s response to the Peterloo massacre.

When the unpopular Prince Regent succeeded to the throne as George IV in January 1820, Wood began corresponding with the new King’s exiled wife, Caroline of Brunswick. In late May he secured an incredible coup over Caroline’s chief advisor, the Whig MP Henry Brougham, who was trying to negotiate a behind-closed doors settlement. Instead, Wood met Caroline in Calais and convinced her to return from exile, take up residence in his London home and from there claim the right to be crowned Queen of the United Kingdom.

Wood returned to London in triumph on 6 June 1820, escorting Caroline in an open carriage through thronging crowds in the metropolis to his South Audley Street home in Mayfair. While the multitude massed daily outside Caroline’s temporary residence, and the great and the good of British radicalism paid her court at South Audley Street, Wood became a loud advocate of his new lodger in the Commons.

When the Tory government agreed to introduce a pains and penalties bill in July 1820, which in effect instituted a divorce trial in the House of Lords, Wood did what over a million of his countrywomen and men would do over the coming months, and signed a petition in support of the Queen. Caroline moved to Brandenburgh House in Hammersmith on 3 August, but Wood remained one of her closest advisors, supporting her throughout her trial in the House of Lords, which ran until November, and leading London’s celebrations in response to the government’s decision to abandon it.

The ‘vulgarity’ and sheer audacity of Wood, who never missed an opportunity to appear at Caroline’s side, shocked the establishment. Many commentators, both Whig and Tory, opined that he was merely seizing an opportunity to secure future patronage. Brougham, for example, continued to denounce Wood as a ‘Jack Ass’ and ‘jobbing fool’.

However, for loyalists such as Theodore Hook (1788-1841), the ultra-Tory prankster and writer, Wood personified the threat posed to the state by the popular radical movement. That the son of a Devonshire chemist had become in effect the landlord of and closest advisor to the Queen seemed at first absurd. However, as the popular movement gathered steam, Wood offered a startling vision of how a world turned upside down might appear – with Caroline as Queen and low-bred Radicals such as Wood in charge at Westminster.

Hook took aim at Wood during 1820 in two widely read satirical pamphlets. The first, Tentamen, portrayed Wood as Dick Whittington, and Caroline as his cat. The second was a six-part poem entitled Solomon Logwood: A Radical Tale. Its publication in October 1820, as Caroline’s trial continued in the Lords, took place after a London-wide march to present two addresses to Caroline at her Hammersmith residence from the ‘married ladies and the inhabitant householders’ of Marylebone.

In the poem Wood was derided as Solomon Logwood, which was in keeping with the punning put-downs of early nineteenth-century doggerel. Rhyming loosely with Alderman Wood (which was Wood’s official title) and referencing his career in the brewing industry and apparent assumption of the duties as a King to Caroline, it translates roughly as king of the beer adulterators – Solomon being the tenth century BC King of Israel and logwood being a common adulterant of beer.

While the invocation of Solomon may be a straightforward biblical allusion (a common nineteenth-century trope), it is likely that for the ultra-Tory Hook the choice of a Jewish king had an added (possibly anti-Semitic) resonance for the overarching theme of his pamphlet, which was to present Wood’s actions as unchristian, unpatriotic and anti-British. In fact, as our previous blog revealed, the pro-Caroline movement was steeped in ‘constitutional language and respect for historic institutions’, a key factor that ensured the movement’s legitimacy.

Hook’s poem tells the story of how Solomon Logwood, at the behest of Satan whispering ‘arise, my son, and earn some fame anew’, brought ‘England’s Queen’ from ‘Italy’s fair clime’ and caused ‘a mighty strife’ from ‘Orkney to Land’s End’. It mocks the ‘good store of rogue and whore’ who had been in South Audley Street ‘each day before the Lady’s door’, and the ‘idle knaves’ and ‘louts’ who since the beginning of Caroline’s trial in August had ‘throng’d all the streets of Westminster and made it like a fair’.

Throughout the poem Wood is chastised for standing ‘o’er her [Caroline’s] ample shoulder’ and ‘blazoning each day the Queen’s approach’ to Westminster during her trial. In the final stanzas he is charged with initiating a mass campaign in favour of Caroline in every ‘market-town’ and ‘each village and high way’ until:

Thus soon they muster’d names enough

of crippled and bed-rid,

brib’d grannies with a pinch of snuff,

and grey-beards with a quid.

Theodore Hook, Solomon Logwood (1820)

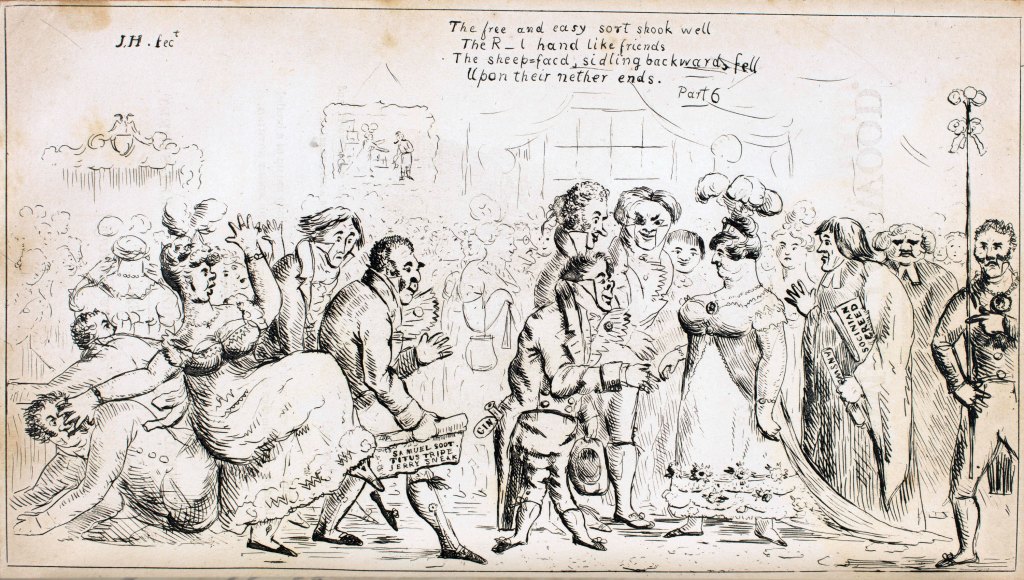

Hook’s satire on the campaign culminated in the presentation of the address to the Queen from the inhabitants of Marylebone, which is the subject of an engraving at the front of the pamphlet. Amidst queueing men and women signatories in the background, Wood stands upright in the far right of the picture, holding a Chamberlain’s wand and wearing a miniature of Caroline around his neck. In the centre Caroline shakes the hand of a ragtag drunkard with a bottle of gin in his pocket, while a man holding an address with the names Samuel Soot, Titus Tripe and Jerry Sneak (a reference to Samuel Foote’s The Mayor Of Garrett), knocks over a woman and causes a crush.

Despite the mockery of critics such as Hook, Caroline continued to receive similar addresses from across the country at her Hammersmith residence, as well as their signatories, while her trial continued in the Lords. Each was accompanied by a festival-like procession, often with tens of thousands in attendance. These events, as well as the huge crowds that continued to gather daily at Westminster, contributed to growing unease in ministerial circles by November and to Lord Liverpool’s eventual decision to drop the bill of pains and penalties.

In the short term, for radicals such as Wood the ensuing mass celebrations in November and December proved short-lived. Without the rallying cry of an unjust divorce, reformers and radicals found it difficult to channel the energy of the pro-Caroline movement into their wider demands for reform. In fact, by January 1821, it was Hook’s loyalist world view that seemed to be in the ascendant, as Tories and moderate Whigs at Westminster and across the country became increasingly confident in their ability to dismiss Caroline and the wider political demands of those who had adopted her cause.

MS

The Solomon Logwood pamphlet is currently on display as part of the Reform, React, Rebel exhibition at UCL, which was curated by Martin and Dr Vivienne Larminie. The exhibition catalogue and a video introducing the exhibition can be viewed online. UCL is currently closed, but the exhibition will be extended following re-opening.

Matthew Wood has three biographical entries for the History of Parliament. His entries in Commons 1790-1820 and Commons 1820-32 are available on our website. For details about how to access the biographies of Wood and other MPs being researched for the 1832-68 project, see here. You can follow The Victorian Commons on Twitter and WordPress to keep up to date with their research.

The History of Parliament will be marking #QueenCaroline200 throughout the summer. Follow the History of Parliament on Twitter for more.

For more on the proceedings in the House of Lords, check out our video: